A Viewing Room: Rho Jae Oon

Online exhibition: Moving Images

Rho Jae Oon, Dear John S#. 01. Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, 25th – 31st May, 2021

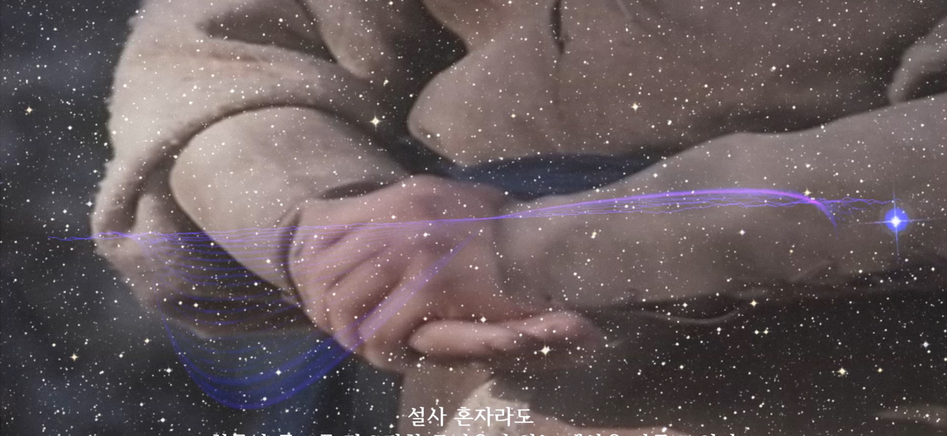

In Dear John S#. 01. Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace (2018), the artist Rho Jae Oon reads cyber-activist and co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation John Perry Barlow’s ‘A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace’ (1996), a manifesto defending early netizens’ rights and freedom against any encroachment from the material world, represented by states and industries. The text read is superimposed on sequences from a virtual journey on Google Earth, itself overlapping with scenes from the North Korean martial arts film Hong Kil-dong (홍길동, 1986) – based on an eponymous novel by sixteenth century politician and scholar Heo Gun – as well as abstract computer-generated animation reminiscent of the early cybernetic cinema of the likes of artists-engineers John and James Whitney and Jordan Belson.

Rho’s work participates in the experimental tradition of the found footage film and of the cinema of appropriation which consists in sampling and re-editing pre-existing cinematic material. Dear John S#. 01. Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace is based on a principle of audio-visual disjunction, the confrontation of the signification of the text with the meaning of the visual footage feeding a dynamic of de-contextualisation and re-contextualisation of the video’s elements to produce an effect of estrangement in the viewer. Ultimately, this strategy defamiliarises meaning by creating new ones. Barlow’s techno-utopian text translates concerns quite symptomatic of its time, the 1990s and the early days of the World Wide Web, aligning with the then widely shared desires and hopes to transcend matter and material realities. As the essay’s concluding sentence has it: ‘We will create a civilisation of the Mind in Cyberspace. May it be more humane and fair than the world your governments have made before.’ Recent history and the environmental costs of data storage, for instance, are enough to contest such cyber-libertarian naivety; however, it is telling of more philosophical problems such as the dualisms between mind and matter, or actuality and virtuality, which seem to be at the core of Rho’s piece. Indeed, in the opening sequences, as we hear Rho reading Barlow’s first paragraph ‘Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone’, we see close shots of the earth. While it is rendered computationally by Google Earth, the images emphasise the earth’s physicality and materiality. Such images of the globe are themselves part of a genealogy of techno-utopian ideas and their visual culture, projects such as the Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalogue and the publication of the first photographic images of the earth from space in 1968 being pivotal moments for conceptions of globalisation and the shrinking of spatial and temporal orders.

If, to some extent, the earth’s shots could be seen as echoing Barlow’s ideas, the former’s superimposition with protagonists and scenes from Hong Kil-dong appear to destabilise these narratives. Considered a kind of Korean Robin Hood, Kil-dong is the illegitimate son of a nobleman and of one of his concubines. Having to leave the household, he is rescued and trained by an old martial arts master. Kil-dong will go on stealing from the rich to give to the poor and fight Japanese invaders. The overlapping imagery from Hong Kil-dong introduces human figures and bodies into the audio-visual landscape of the work, as well as questions of class struggle and autonomy.

Around the middle, the video shifts to a Google Maps shot on Paul Cézanne’s studio in Aix-en-Provence, France, subsequently reverting its vertical vision to a horizontal one, the viewer then being taken around the neighbourhood. This also seems to refer to questions around the actual and the virtual. Writing about Cézanne in his book on Francis Bacon, philosopher Gilles Deleuze contended that ‘psychic clichés’ and ‘ready-made perceptions’ pre-exist their re-formatting on a canvas, taking as example Cézanne’s internal and external milieus: ‘The painter has many things in his head, or around him, or in his studio. Now everything he has in his head or around him is already in the canvas, more or less virtually, more or less actually, before he begins his work.’*

Finally, it is difficult not to see in Dear John S#. 01. Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace a nod to the Situatonist artist René Viénet’s film Can Dialectics Break Bricks? (1973). Indeed, Viénet already overlayed footage from a Hong-Kongese martial art films with a voice over iterating Marxist theory, an example of the Situationist strategy of détournement. Viénet saw in the latter applied to vernacular cinema the possibility to realise Marx’s critique of political economy, dubbing the characters’ voices which became vehicles for the diffusion of the proletarian critique of bourgeoisie. In this regard, Rho’s can be seen as an attempt at updating the strategy of détournement in the context of cybernetic capitalism, of which, with the current generalised pervasiveness of screens, we seem to be witnessing an updated version.

* Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon. The Logic of Sensation, London: Continuum, 2002, p. 86.

Artist Bio:

Rho Jae Oon has produced a number of web-based projects including Vimalaki.net, AEGIPEAK, Bite the Bullet! and God4saken. Rho has had solo exhibitions at Insa Art Space, Art Space Pool, Gallery Plant and Atelier Hermès. He participated in numerous group exhibitions at venues such as PLATEAU, the Samsung Museum of Art and the New Museum. His work has been presented in international biennials including SeMA Biennale (2014), Busan Biennale (2012) and the Gwangju Biennale (2006). Rho is currently a director of C12 Pictures.

Credit:

This video has been selected by Adeena Mey.