UNESCO World Heritage in Korea

KCCUK Culture Series

We explore Korea's rich cultural heritage as recognised by UNESCO, from protected palaces and temples to intangible traditional culture and the documents that shed light on national history.

UNESCO in Korea

In 1972, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) established the World Heritage List with the purpose of protecting cultural and natural heritage sites in all corners of the globe – sites whose conservation is recognised to be in the interests of all of humanity.

Since then Korea has come to occupy a prominent position on this world list, with a current total of 13 cultural heritage sites and one natural heritage site (Jeju Island). In addition, UNESCO has recognised twenty important aspects of Korean traditional culture on its Intangible Cultural Heritage List, and sixteen significant historical documents on its Memory of the World List.

The UNESCO lists are a great place to start when exploring Korean history and culture, either on your trip to Korea or from home. You can find a comprehensive list of the recognised Korean heritage sites and cultural traditions on the Korea Tourism Organisation website, but in this article we have selected a few prominent examples from each category as an initial introduction to the vibrant cultural heritage of Korea.

Royal heritage: the UNESCO palaces, fortresses and tombs

The historical background of Korea’s cultural heritage sites is diverse, spanning from the truly ancient Gochang, Hwasun and Ganghwa Dolmen Sites (prehistoric funerary and ritual monuments) to the multiple sites built during the more recent Joseon Dynasty (1392 – 1897).

As you’ll notice if you visit Korea, many of the most prominent historical sites are associated with the royal families that governed Korea in the past, from palaces and fortresses to magnificent royal tombs. Here are a few that have made it onto the UNESCO World Heritage List (with the dates indicating when they were added):

- Jongmyo Shrine (1995) – Jongmyo is the royal ancestral shrine of the Joseon Dynasty and is located in Jongno-gu, central Seoul. Its two main buildings – Jeongjeon Hall and Yeongnyeongjeon Hall – exhibit the unique architectural style of 16th century Korea, and still host seasonal memorial rites commemorating the lives and achievements of the royal ancestors of Joseon.

- Changdeokgung Palace Complex (1997) – Changdeokgung Palace, also located in Jongno-gu, is one of the five Royal Palaces of Joseon. It was built in 1405 as a royal villa but became the Joseon Dynasty’s official royal residence after Gyeongbokgung was destroyed by invading Japanese forces in 1592. The palace maintained its prestigious position until 1867. Visitors often enjoy the peaceful atmosphere of the ‘Secret Garden’ tucked behind the buildings of Changdeokgung.

- Hwaseong Fortress (1997) – Located in Suwon, Gyeonggi-do Province, this large fortress was constructed in 1796 by King Jeongjo after he moved the grave of his father, Crown Prince Sado, to Suwon. The fortress was built to effectively protect the city using scientific devices developed by the distinguished Confucian thinker and writer Jeong Yak-yong, including the Geojunggi crane and the Nongno pulley wheel.

- Royal Tombs of the Joseon Dynasty (2009) – The Joseon Dynasty left behind a total of 44 tombs occupied by Kings and their Queen Consorts, most of which are located near the capital in Gyeonggi-do Province. The tombs are recognised for reflecting the values of the Korean people (drawn partly from Confucian ideology and fengshui), as well as for being preserved in their original condition for up to 600 years.

The Buddhist and Confucian sites recognised by UNESCO

Buddhism has occupied a prominent place in Korean culture since it first arrived in 372, with the first two temples built in 375 by King Sosurim of Goguryeo and many more to follow. Owing to their particular historical significance, a handful of Korean Buddhist temples are listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List and are among the most popular tourist attractions in Korea.

Another strong influence on Korean culture and society is Neo-Confucianism, an ideology which melds the older teachings of Confucius with Taoism and Buddhism, and which began to take hold during the Goryeo Dunasty (918-1392) before being adopted by the Joseon state as its primary belief system. The significance of Neo-Confucian ideology throughout Korean history led to UNESCO’s recognition of nine Korean seowon, Neo-Confucian academies, as a World Heritage Sites in 2019.

Buddhist and Confucian sites on the UNESCO list include:

- Haeinsa Temple Janggyeong Panjeon, the Depositories for the Tripitaka Koreana Woodblocks (1995) – The printing woodblocks of the Tripitaka Koreana (Buddhist scriptures produced during the Goryeo Dynasty, 918-1392) are housed in two specially made depositories at Haeinsa Temple in Hapcheon. The depositories are recognised for their unique design which makes use of the wind blowing in from the valley of Gayasan to provide effective natural ventilation and ensure the safe storage of the woodblocks.

- Seokguram Grotto and Bulguksa Temple (1995) – Seokguram in Gyeongju, Gyeongbuk Province is a Buddhist hermitage with an artificial stone cave built in 774 to serve as a dharma hall. The grotto’s Buddha statue, surrounded by carvings of his guardians and followers, is widely admired as a masterpiece. Built in the same year, Bulguksa Temple houses a variety of exquisite monuments including two stone pagodas, Dabotap and Seokgatap, the latter of which is generally regarded as the archetype of all three-story stone pagodas built across Korea thereafter.

- Sansa, Buddhist Mountain Monasteries in Korea (2018) – Sansa consists of seven Buddhist mountain monasteries: Tongdosa, Buseoksa, Bongjeongsa, Beopjusa, Magoksa, Seonamsa and Daeheungsa. Established between the 7th and 9th centuries, the monasteries have since functioned as centres of religious belief, spiritual practice, and daily living of monastic communities, reflecting the distinct historical development of Korean Buddhism.

- Seowon, Korean Neo-Confucian Academies (2019) – This site comprises nine traditional Korean Neo-Confucian Academies, known as ‘seowon’, built across the central and southern parts of Korea during the Joseon Dynasty. The academies, according to UNESCO, are “exceptional testimony to cultural traditions associated with Neo-Confucianism in Korea”.

Jeju Island: A World Natural Heritage Site

Jeju Island, the largest island in Korea boasting a temperate climate and beautiful natural scenery, has always been a popular tourist destination with Korean and foreign visitors alike. In 2007, Jeju was designated a World Natural Heritage Site under the name “Jeju Volcanic Island and Lava Tubes”. The UNESCO-recognised site includes three specific features formed by the island’s volcanic structure: Mount Halla, the Geomunoreum Lava Tube system and Seongsan Ilchulbong Peak.

- Mount Halla – Hallasan, or Mount Halla, is Korea’s tallest mountain and is recognised for its beautiful array of textures and colours that appear throughout the changing seasons.

- Geomunoreum Lava Tubes – the Geomunoreum Lava Tube system is regarded as the most impressive of its kind in the world. The tubes present an outstanding visual impact, with their unique spectacle of multi-coloured carbonate decorations adorning the roofs and floors, and dark-coloured lava walls that are also partially covered by a mural of carbonate deposits.

- Seongsan Ilchulbong – Seongsan Ilchulbong is a tuff cone formed by hydrovolcanic eruptions over 5,000 years ago. Originally a separate island, it has become naturally connected to the main island over time and is now one of Jeju’s most dramatic landscape features, often said to resemble a gigantic ancient castle. Ilchulbong means ‘sunrise peak’, and true to its name visitors who climb the peak early enough are treated to a magnificent sunrise.

Preserving Korean traditions through Intangible Cultural Heritage

Alongside the temples, palaces and natural sites listed above, UNESCO also recognises Korea’s Intangible Cultural Heritage, a category defined as: “traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants” and incorporating oral traditions, performing arts, rituals, festive events, the skills to produce traditional crafts and more.

As of 2020 UNESCO has recognised twenty examples of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Korea, which is testament to the country’s unique cultural history and preservation of traditions. We have selected just a few prominent examples to introduce here.

- Pansori Epic Chant (2003) – Often referred to as ‘Korean Opera’, pansori is a genre of musical storytelling performed by a vocalist and a drummer. The art form, which was established during the 18th century, combines singing (sori) with gestures (ballim) and narrative (aniri) to present an epic drama conceived from popular folk tales and well-known historic events. Watch UNESCO’s short explanatory video of pansori here.*

- Ganggangsullae Dance (2009) – The Ganggangsullae dance was traditionally performed by women around the coastal areas of Jeollanam-do during traditional holidays such as Chuseok and Daeboreum. Performers sing the song of Ganggangsullae as they dance, alternating between the lead singer and the rest of the group with the song tempo and dance movements becoming faster towards the end. Find out more about the dance in UNESCO’s video here.

- Taekkyeon, a traditional Korean martial art (2011) – Also known as Gakhui (sport of legs) and Bigaksul (art of flying legs), Taekkyeon is aimed at improving one’s self-defence techniques and promoting physical and mental health through the practice of orchestrated dance-like bodily movements, using the feet and legs in particular. Watch UNESCO’s video of Taekkyeon here.

- Arirang, lyrical folk song in the Republic of Korea (2012) – Arirang is a well known and beloved Korean folk song whose simple musical and literary composition invites improvisation, imitation and singing in unison, encouraging its acceptance by a variety of musical genres. Each region of the country has its own celebrated version of the song with different lyrics, creating both cultural diversity and unity across Korea. Listen to some of the different versions in UNESCO’s video here.

- Kimjang, making and sharing kimchi (2013) – Traditionally Kimjang takes place in autumn, when families and sometimes whole communities get together to prepare enough kimchi to last the cold winter. While kimchi can now easily be bought from a supermarket at any time of year, the age-old tradition of Kimjang is still maintained in Korea as a collective cultural activity contributing to a shared sense of social identity. See how kimchi is made during the Kimjang season here.

- Culture of Jeju Haenyeo, women divers of Jeju Island (2016) – Jeju Island is home to a community of women, some over 80 years old, who dive substantial depths into the sea without the support of oxygen masks to gather abalone, sea urchins and other shellfish. The haenyeo go diving for up to seven hours a day, 90 days of the year, holding their breath for up to two minutes and making a unique verbal sound when they resurface. Witness their incredible skill and stamina in UNESCO’s video here.

*All videos were produced courtesy of the Korean Cultural Heritage Administration before being uploaded to the official UNESCO YouTube Channel.

Documenting Korean history: The Memory of the World Register

The final UNESCO list we’d like to introduce is the Memory of the World Register, launched to protect and preserve the documentary heritage of humanity. The list includes written works, maps, musical scores, films, and photographs.

A total of sixteen Korean documents are currently listed on the register, all of which shed crucial light on different events in Korean history from the Goryeo Dynasty (918 – 1392) up until the late 20th century. Here are a few representative examples:

- Hunminjeongeum Manuscript (1997) – Hunminjeongum is the manuscript published in the ninth lunar month of 1446 which contains King Sejong’s promulgation of the Korean alphabet, now known as hangeul. The document currently resides in the Kansong Art Museum in Seoul. To find out more about the history of the Korean alphabet read our earlier Culture Series entry on Hangeul, a Script with No Equal.

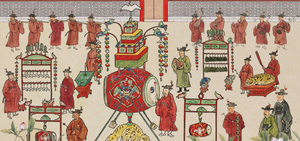

- Uigwe, the Royal Protocols of the Joseon Dynasty (2007) - A unique form of documentary heritage, the "Uigwe" is a collection of royal protocols of the Joseon Dynasty (1392 – 1910) which both records and prescribes through prose and illustration the major ceremonies and rites of the royal family. Earlier this year we presented a media showcase of the Kisa chin p'yori chinch'an ŭigwe manuscript in our exhibition From Tangible to Intangible - and you can view a digital version of the manuscript at the British Library website (link below).

- Human Rights Documentary Heritage 1980 Archives for the May 18th Democratic Uprising against Military Regime in Gwangju (2011) – This is a collection of items including written documents, photos and images which document the May 18th Democratic Uprising in Gwangju. The Gwangju Uprising not only played a pivotal role in the democratization of Korea, but also inspired several other pro-democracy movements across East and Southeast Asia in the 80s and 90s.

- The Archives of the KBS Special Live Broadcast “Finding Dispersed Families” (2015) – This comprises 20,522 records of live broadcasts by KBS (the Korean Broadcasting System) of war-dispersed families being united between June and November 1983. The KBS broadcast raised widespread recognition in Korea and around the world of the deep scars left by the Korean War (and more widely, the Cold War) on families and individuals.

Top image Hwaseong Fortress © Korea Tourism Organization