100 Years of Korean Cinema

Korean Classic Film Recommendations

Celebrate the 100 year anniversary of Korean cinema with classic titles available on the Korean Film Archive YouTube channel.

Last year’s London Korean Film Festival celebrated a century of Korean cinema from 1919 to 2019, honouring this milestone with a unique programme of UK and European premieres showcasing culturally important titles from throughout Korean film history.

The Korean Film Archive has made a huge database of classic films available on its YouTube channel with English subtitles. We've put together a list of some of the most influential and important films from each decade to narrow down your list - although we encourage you to explore the YouTube channel yourself to discover more hidden gems as well.

The 1930s

Sweet Dream (Lullaby of Death) (미몽 – 죽음의 자장가 | 1936 | Yang Ju-Nam)

One of the few lost films from the Japanese colonial era (1910-45) that has been rediscovered in recent years tells the story of Ae-sun, the vain wife of a middle-class man who has no interest in looking after her family and is chased out by her husband, only to find out her lover is not the prosperous entrepreneur she thought he was but a poor student and criminal.

The 1940s

Tuition (수업료 | 1940 | Choi In-Gyu)

A film based on the memoir of a fourth-grade student who received the grand prize in a writing contest sponsored by the Gyeongseong Daily. A boy, whose parents sell brass spoons on the street while his grandmother is sick in bed, struggles to find money for his tuition.

Spring of the Korean Peninsula (반도의 봄 | 1941 | Lee Byung-Il)

A young filmmaker and his crew struggle to bring the famous Korean story of Chunghyang to the big screen. The film allows a fascinating insight into the complexities of filmmaking in Korea in the 1940s, and via posters on the studio walls indicates the wide variety of film influences, from German expressionism to Hollywood dramas, that Korean directors in this period had.

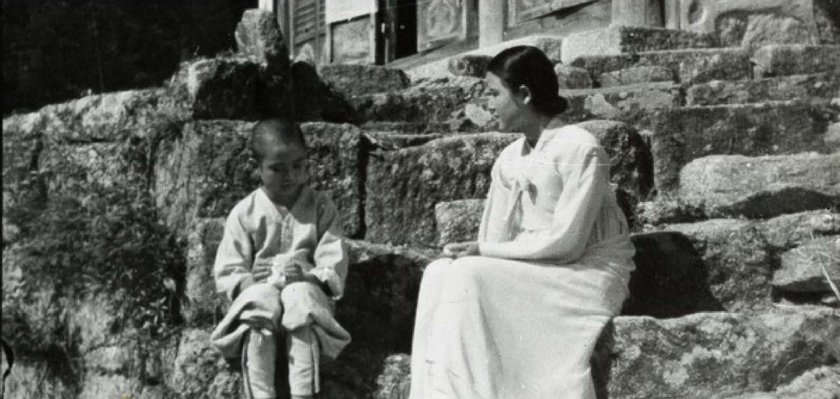

A Hometown of the Heart (마음의 고향 | 1949 | Yoon Yong-Kyu)

A touching yet subtly presented story of a boy in a Buddhist temple hoping to find his mother. One of the few surviving works from the politically turbulent period of the late 1940s, just before the outbreak of the Korean War (1950-53).

The 1950s

Piagol (피아골 | 1955 | Lee Kang-Cheon)

This decade saw the first major attempt in cinema to confront the recent war and its ideological divisions. Piagol focuses on partisan Communist fighters based in the South who, hiding in the mountains, continued to fight on behalf of the North.

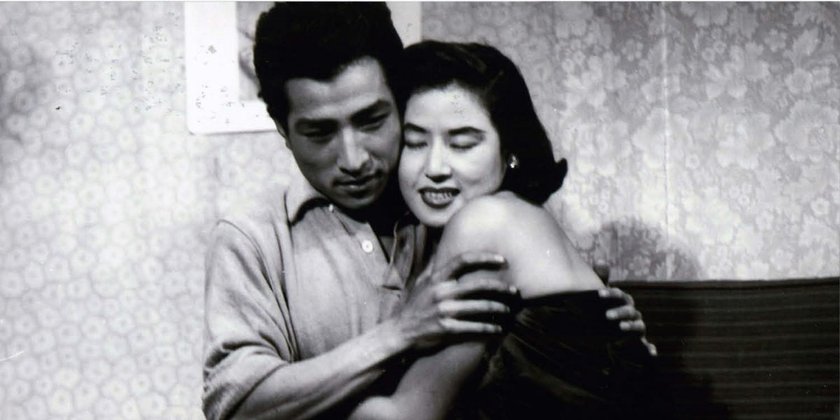

Madame Freedom (자유부인 | 1956 | Han Hyeong-Mo)

Films of the 1950s confronted some of the key issues facing Korean society as it rebuilt itself anew. Like Madame Freedom, an adaptation of the decade’s most scandalous serial novel, many centred on women who symbolised the tension between collapsing traditional values and the influence of Western capitalism. The box-office success of this film encouraged a renewed flow of investment into a film industry hit hard by the war.

The Flower in Hell (지옥화 | 1958 | Shin Sang-Ok)

Inspired by both Italian Neorealism and Hollywood genre films, The Flower In Hell paints a hard-edged portrait of a broken city where the only way to get ahead was to break the law.

The 1960s

Aimless Bullet (오발탄 | 1961 | Yoo Hyeon-Mok)

Filmmakers took advantage of weakened censorship in the 1960s to introduce more pointed social criticism into their films. This certainly applies to Aimless Bullet, a searing depiction of the economic wasteland of post-war Seoul whose brooding pessimism and superlative filmmaking helped establish it as an all-time classic.

A Woman Judge (여판사 | 1962 | Hong Eun-Won)

“I will defend her to the end!” Heo Jin-suk, the titular protagonist of Hong Eun-won’s first film – and only the second Korean feature by a woman director – is defending her mother-in-law who has confessed to murder, but she could be speaking for all women’s rights.

The Seashore Village (갯마을 | 1965 | Kim Su-Yong)

Introduced at the Opening Gala of last year’s LKFF, The Seashore Village follows the story of a beautiful fishing village home to a community of widows who have lost their loved ones at sea. This was one of the earliest successful munye (literary adaptation) films, a genre which would come to define much of South Korean cinema during the 1960s.

The 1970s

Woman of Fire (화녀 | 1971 | Kim Ki-Young)

Woman of Fire (recommended by film critic Anton Bitel) sees Kim Ki-Young remake his stunning classic The Housemaid (1960) with an energy and passion that would come to define Korean cinema of the 1970s. Focusing on the role women play within the home, the film follows a composer and his wife, whose lives are thrown into turmoil by the introduction of a new housemaid.

Hometown of Stars (별들의 고향 | 1974 | Lee Jang-Ho)

Lee Jang-ho’s sensational debut introduced his sardonic experimental style and focus on socially relevant cinema, through the story of a woman who turns to alcoholism after suffering a torrent of emotional and physical abuse from men.

The March of Fools (바보들의 행진 | 1975 | Ha Gil-Jong)

Ha Gil-jong’s penultimate film starts off as a bawdy comedy, as two drunk students try to get laid with varying degrees of success. Slowly the tone becomes melancholy as they consider their destinies in a repressive society where they feel out of place.

The 1980s

People of the Slum (꼬방동네 사람들 | 1982 | Bae Chang-Ho)

A shantytown south of Seoul has collected poor people and misfits from all over the country into its twisting alleyways. Myeong-suk is known as ‘black glove’: she wears that glove on a hand severely burnt while saving her baby boy from a horrible injury. For his debut film Bae planted a love triangle inside a Korean neo-realist setting where poverty pokes sharp elbows into the basic decency of ordinary people. The film’s success launched him into a career as the most popular director of the 1980s.

Ticket (티켓 | 1986 | Im Kwon-Taek)

Min Ji-sok (Kim Ji-mee) is the no-nonsense owner of a cafe in the tough port town of Sokcho. Her ‘girls’ serve more than tea or coffee, if a male customer purchases the right ticket. Against the background of the women’s sorrows and moments of happiness, we learn the story of how Ji-sok herself ended up in dead-end Sokcho.

The Age of Success (성공시대 | 1988 | Jang Seon-Woo)

A year after the release of Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987) with its sardonic credo of “greed is good”, director Jang Seon-Woo unveiled what looks three decades on like the Korean response – a vivid, madcap comedy of corporate intrigue and naked self-advancement.

The 1990s

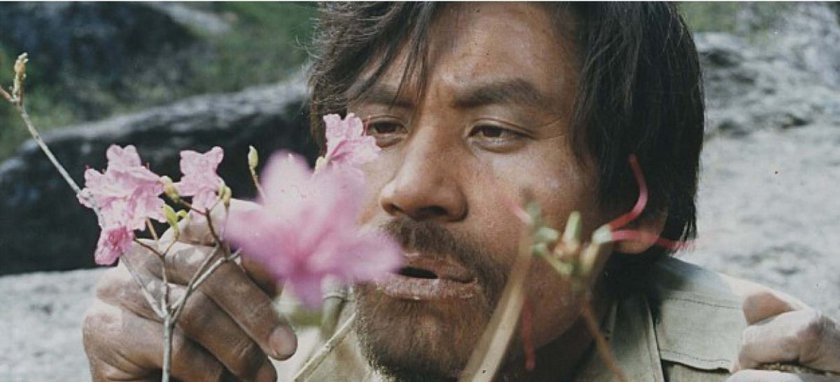

North Korean Partisan in South Korea (남부군 | 1990 | Chung Ji-Young)

Director Chung Ji-Young captures a previously rarely seen aspect of the Korean War, focusing on the North Korean side of the conflict. Based on the experiences of real-life war correspondent Lee Tae, the film illuminates the struggles of the men and women, soldiers and civilians fighting for survival in the conflict – portrayed as inherently human, whichever side they’re on.

Seopyonje (서편제 | 1993 | Im Kwon-Taek)

This musical drama tells the story of a family of pansori (traditional Korean opera) singers trying to make a living in the modern world. It broke box office records to become the first Korean film to draw audiences of over one million and helped revive popular interest in traditional Korean culture.

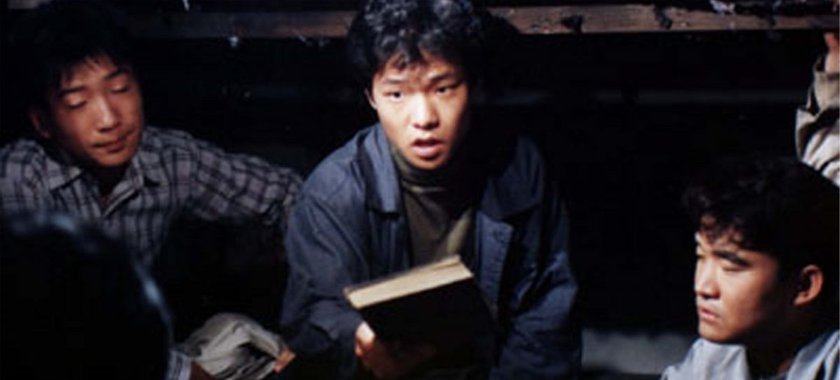

A Single Spark (아름다운 청년 전태일 | 1995 | Park Kwang-Su)

This seminal protest drama by Korean New Wave filmmaker Park Kwang-Su offers two narratives: the true story of young textile factory worker and activist Jeon Tae-il, who famously set himself ablaze in 1970, and the partly fictionalized efforts of another activist, who five years later tries to commit Jeon’s tale to the page while evading capture. The film was co-written by none other than the future Korean cinema masters Lee Chang-dong and Hur Jin-ho.